The Chesapeake Bay is a historic estuary residing within the states of Maryland and Virginia, whose influence as a major body of water ranges from providing ample fisheries to vast space for recreational activities. It is a hallmark of American history, and it is dying.

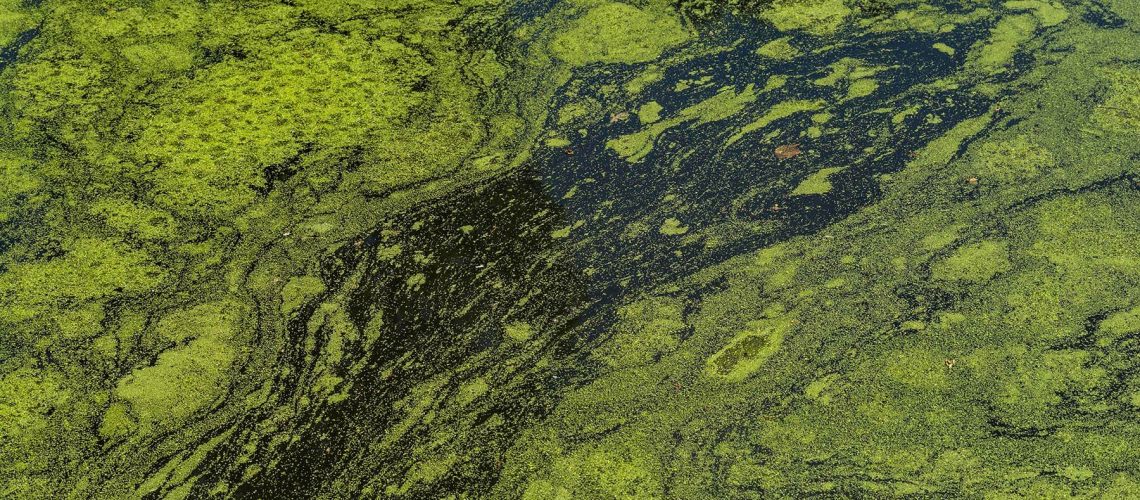

Dead zones in the Chesapeake Bay have been an ongoing and worsening phenomenon for decades, decreasing the estuary’s dissolved oxygen by over 2% in the past 50 years. Dead zones occur when there is runoff from nearby farms where synthetic fertilizers, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, are abundant in the soil. This readily available form of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizes algal populations in the Chesapeake and eventually leads to an algal bloom, or an abundance of algae growing near the top of the water on the estuary (phenomenon known as eutrophication). This algal bloom creates a barrier between the sunlight and the water and can be very detrimental to underlying photosynthetic organisms. Furthermore, once the algae start to die and decompose, the high levels of decomposition by microbes in the water utilize much of the estuary’s oxygen, further compromising other organisms by decreasing fundamental oxygen levels and selecting for species with tolerance to lower concentrations of oxygen. Alongside runoff from local farms, dead zones in the Chesapeake are also supplemented by wastewater treatment plants and urban stormwater runoff. The water runoff from these sources works in a similar way, containing heavy amounts of organic matter ready to decompose in the estuary’s water. This is a process whereby oxygen is consumed at high rates and therefore deprived from the surrounding environments and their organisms, which can be very problematic as species dwindle and biodiversity becomes compromised. The dead zone that results is one where very little, if any, species remain in an area of water due to the area’s deprivation of sunlight and ultimately oxygen. Recently, the issue of dead zones has been worsened by the increasingly problematic trend of global warming. As the earth and the oceans warm, oxygen becomes less soluble in water and thus precipitates out, further deepening the effects of eutrophication and chemical runoff on the Chesapeake Bay.

The formation of dead zones within the Chesapeake Bay is not only an aesthetic matter. The sharp decrease in biodiversity has countless consequences on nearby human populations and on both the state-wide and national economies. With a decrease in biodiversity and a major die-off event, many fisheries are nearly emptied. The Chesapeake Bay is a major source of these fisheries, so their diminishment can be very detrimental to both the local and national economies, weakening the fishing industry and putting many workers out of jobs. Furthermore, dead zones are high in organic material and synthetic chemicals, and thus their heavily polluted nature repels tourism. As fisheries dwindle, the fish that remain or that are able to survive under low oxygen conditions in areas nearby to the dead zones are prone to high levels of bioaccumulation over time. That is to say, as organisms lower in the food chain consume the high levels of chemical pollution in the estuary, those organisms near the top of the food chain (e.g. big fish, salmon) bioaccumulate this pollution in their systems by eating “contaminated” organisms. This creates a critical health hazard for nearby human populations that rely on local fisheries as their source of seafood. If there is bioaccumulation over time in the fish that are most popularly consumed by humans, then this bioaccumulation is prone to get translated into our systems upon consumption. Oftentimes, the chemicals that reside in dead zones alongside phosphorus and sulfur can include mercury, which can be very compromising to one’s health if chronically ingested and has been shown in several studies to be carcinogenic.

With the increasing tendency of dead zones in the Chesapeake Bay, there is a parallel restorative effort. Currently, organizations such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation are working to restore the historic estuary by educating the public on the components of dead zones and their negative effects on both the environment and economy, working to rescue endangered native species such as oysters and underwater grasses, and planting trees near the estuary to serve as filters for the chemical runoff. In addition, local movements by citizens have prompted the creation and reinforcement of environmentally-friendly legislation to protect the Chesapeake Bay, fighting back attempts from the EPA to rollback restrictions on nitrogen pollution, a decision which could harm not only the Chesapeake Bay but also other vulnerable water sources across the nation. In this attempt at educating the public and reinforcing environmental laws, much of the local public has been made aware of the fundamentality of the Chesapeake Bay in various aspects of human life, and thus there have also been self-started efforts by various local farmers to reduce the usage of synthetic fertilizers on their land and implement the usage of organic fertilizers whenever possible.

Although dead zones are indubitably an issue of concern not only within the Chesapeake Bay but also globally, the increased public awareness of their detrimental nature has incited positive change in reducing and perhaps even reversing the conditions that feed these dead zones. With sufficient legislation, motivation, and public education, the dead zones in the Chesapeake Bay and those of other water bodies can be reversed, and their natural integrity rescued.

Dance, S. (2018, January 7). Scientists say ‘dead zones’ like those in Chesapeake have grown four-fold across oceans, threaten marine life. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/environment/bs-md-ocean-oxygen-study-20180105-story.html

Dance, S. (2019, June 12). Chesapeake Bay’s ‘dead zone’ forecast to be among largest in decades during summer 2019. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/environment/bs-md-chesapeake-dead-zone-20190612-story.html

Dead zones. (n.d.). Retrieved February 3, 2020, from National Geographic website: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/dead-zone/

How we save the bay. (n.d.). Retrieved January, 2020, from Chesapeake Bay Foundation website: https://www.cbf.org/how-we-save-the-bay/

Scheer, R. (2012, September 12). What causes ocean “dead zones”? Scientific American. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ocean-dead-zones/Smith, S. (2015, June 23).

Scientists predict smaller than average dead zone for Chesapeake Bay. Chesapeake Bay Program. Retrieved from https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/scientists_predict_smaller_than_average_dead_zone_for_chesapeake_bay1